Amy L. Eva, Ph.D.

The education content specialist at the Greater Good Science Center.

Even the best work can wear us down. How do we find inspiration and purpose again?

What gives you a sense of meaning in your work, even on the tough days?

When I posed this question to a group of teachers recently, no one focused on academics. Instead, their responses centered on their students’ engagement, the sense of participating in something larger than themselves, and the deep satisfaction they gained from relationship building.

“When my students make me laugh, and when they do

that ‘oooooooooohhh’ sound that kids do when they finally ‘get’ it,”

confessed a fifth-grade teacher. “Knowing the work you do is bigger than

yourself is what keeps me motivated,” said a university professor.

“When my students make me laugh, and when they do

that ‘oooooooooohhh’ sound that kids do when they finally ‘get’ it,”

confessed a fifth-grade teacher. “Knowing the work you do is bigger than

yourself is what keeps me motivated,” said a university professor.

A 20-year veteran kindergarten teacher said this: “It’s still the relationships I build every year that give me the most meaning. … Even now I get in the car at the end of the day and think, What was great about today? What was hard? How can I improve tomorrow?”

If you are feeling a bit worn down right now and need some inspiration, here are five practical ways to pause, reflect on your work, reconnect with your role and purpose. It hopefully goes without saying that these tips aren’t just for teachers—they can be adapted by almost anyone who needs to reignite his or her passion for work.

Teachers connecting at the Greater Good Science Center’s Summer Institute for Educators

We can’t do this alone. And there are lots of opportunities to connect (especially

if you feel like you don’t have the time). I know groups of teachers

who meet weekly at a restaurant or bar to grade papers and talk. I know

teachers who run together, meditate together, and camp together.

Teachers connecting at the Greater Good Science Center’s Summer Institute for Educators

We can’t do this alone. And there are lots of opportunities to connect (especially

if you feel like you don’t have the time). I know groups of teachers

who meet weekly at a restaurant or bar to grade papers and talk. I know

teachers who run together, meditate together, and camp together.

There are also many more formal opportunities to grow professionally and personally, meet new colleagues, and develop networks of support. For example, you can take an online course at Mindful Schools, participate in the CARE retreat for teachers, or apply to join us for the Summer Institute for Educators here at UC Berkeley. A new year-long program called Transformational Educational Leadership is also inviting applications.

Bottom line, reach out (even when it’s tough). Nurture new friendships while pursuing new professional development options.

A recent report by the Aspen Institute, “The Evidence for How We Learn,” makes it crystal clear: “For social, emotional, and academic development to thrive in schools, teachers and administrators need … support to understand and model these skills, behaviors, knowledge, and beliefs.” Children learn social-emotional skills by being exposed to adult behavior. “If a teacher doesn’t have a level of social-emotional competence … then he or she is sending mixed messages,” writes Patricia Jennings, in her book Mindfulness for Teachers.

In addition to seeking out social support, there are many other research-based strategies for self-care, including physical exercise, mindfulness, self-compassion, and cognitive reappraisal (reframing your thoughts in response to a challenging exchange with a student, for example). There’s also a place for just forcing yourself to get up and go to that party even though you want to curl up in a ball on the couch—a technique psychologists call behavioral activation.

“Self-care is not a luxury,” write John Norcross and James Guy. “It is a human requisite, a professional necessity, and an ethical imperative.”

When I posed this question to a group of teachers recently, no one focused on academics. Instead, their responses centered on their students’ engagement, the sense of participating in something larger than themselves, and the deep satisfaction they gained from relationship building.

Ingin dapat tambahan uang dengan modal hanya 25 ribu rupiah, bisa

menghasilkan Rp.800 Juta,- Dari Bisnis Iklan ?

Silahkan klik : https://muslimpromo.com/?ref=8076

Silahkan klik : https://muslimpromo.com/?ref=8076

A 20-year veteran kindergarten teacher said this: “It’s still the relationships I build every year that give me the most meaning. … Even now I get in the car at the end of the day and think, What was great about today? What was hard? How can I improve tomorrow?”

If you are feeling a bit worn down right now and need some inspiration, here are five practical ways to pause, reflect on your work, reconnect with your role and purpose. It hopefully goes without saying that these tips aren’t just for teachers—they can be adapted by almost anyone who needs to reignite his or her passion for work.

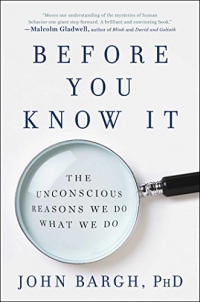

1. Revisit your story

Researchers remind us that having a purpose in life is crucial for our health, longevity, and well-being. At the Greater Good Science Center’s Summer Institute for Educators, we invite educators to reflect more deeply on their purpose and identity in the following activity, which you can do at home (in your pajamas with your favorite beverage):- Create a brief timeline of several major events, turning points, and epiphanies that made you the person and education professional you are today.

- Choose two or three of these events and reflect on each one. What feelings do you associate with the event? What lessons emerged for you? What obstacles and supports did you encounter? Did you learn anything about your strengths, weaknesses, motives, and values from this event?

- Overall, what story does your timeline tell about who you are?

2. Celebrate a favorite teacher or mentor

Here is another simple exercise to try at home or in a staff meeting. If you try this activity with colleagues, partner up and stand back to back while listening to each question read aloud; next, turn and face each other as you share your responses. The process of pausing, reflecting, and then listening to your partner, in close proximity, may help you to focus more on the words and emotions shared.- Describe the teacher or mentor who had the most influence on you.

- How did you feel when you were with this person?

- How did you change as a result of this person?

- How did this person shape your life as an education professional?

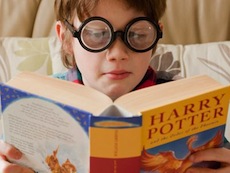

3. Connect with like-minded colleagues

When I talk with teachers, I often recall an image of myself during my first year of high school teaching. I would escape into my little cubby-hole of an office at lunchtime and lie flat on my back with the lights out. I felt totally overwhelmed and isolated that year; I was trying my hardest to meet the needs of 163 students every day, and I was physically and emotionally exhausted. The principal stepped into my classroom only once that year, and the teachers down the hall kept to themselves. Teachers connecting at the Greater Good Science Center’s Summer Institute for Educators

Teachers connecting at the Greater Good Science Center’s Summer Institute for Educators

There are also many more formal opportunities to grow professionally and personally, meet new colleagues, and develop networks of support. For example, you can take an online course at Mindful Schools, participate in the CARE retreat for teachers, or apply to join us for the Summer Institute for Educators here at UC Berkeley. A new year-long program called Transformational Educational Leadership is also inviting applications.

Bottom line, reach out (even when it’s tough). Nurture new friendships while pursuing new professional development options.

4. Prioritize your well-being

If you are a teacher, there are probably plenty of obstacles preventing you from engaging in self-care. We teachers are notoriously resistant to helping ourselves out. So perhaps the argument below might convince you that your personal and professional well-being must be your number one imperative.A recent report by the Aspen Institute, “The Evidence for How We Learn,” makes it crystal clear: “For social, emotional, and academic development to thrive in schools, teachers and administrators need … support to understand and model these skills, behaviors, knowledge, and beliefs.” Children learn social-emotional skills by being exposed to adult behavior. “If a teacher doesn’t have a level of social-emotional competence … then he or she is sending mixed messages,” writes Patricia Jennings, in her book Mindfulness for Teachers.

In addition to seeking out social support, there are many other research-based strategies for self-care, including physical exercise, mindfulness, self-compassion, and cognitive reappraisal (reframing your thoughts in response to a challenging exchange with a student, for example). There’s also a place for just forcing yourself to get up and go to that party even though you want to curl up in a ball on the couch—a technique psychologists call behavioral activation.

“Self-care is not a luxury,” write John Norcross and James Guy. “It is a human requisite, a professional necessity, and an ethical imperative.”

5. Create a resilience plan

Of course, developing social-emotional skills takes time, and resilience is an ongoing, dynamic process of adaptation and growth. So, why not create a plan?- Consider (or try out) some of the research-based practices above.

- Notice which ones seem appealing, enjoyable, or helpful.

- Think about how you might incorporate one of these into your life.

- Choose one self-care strategy or practice to implement in your daily life (or almost every day) for at least 5-10 minutes. (Keep it simple.)

- What kinds of obstacles and barriers might arise? How might you address those obstacles? How will you encourage yourself to prioritize this plan?

© jonapotkivanunk.hu

© jonapotkivanunk.hu