Jeremy Adam Smith

UC Berkeley

We know in our gut when we’re hearing a good story—and research is starting to explain why.

Stories are told in the body.

It doesn’t seem that way. We tend to think of stories as emerging

from consciousness—from dreams or fantasies—and traveling through words

or images to other minds. We see them outside of us, on paper or on

screen, never under the skin.

(You still have problem with your financial? May be this is a solution: https://muslimpromo.com/?ref=8076)

© jonapotkivanunk.hu

© jonapotkivanunk.hu

But we do

feel stories. We know in our gut when we’re hearing a good one—and science is starting to explain why.

Experiencing a story alters our neurochemical processes, and stories

are a powerful force in shaping human behavior. In this way, stories are

not just instruments of connection and entertainment but also of

control.

We don’t need the science of storytelling to tell a story. We do,

however, need science if we want to understand the roots of our

storytelling instinct and how tales shape beliefs and behavior, often

below conscious awareness. As we’ll discuss, science can help us to

defend ourselves in a world where people are constantly trying to push

our buttons with the stories they tell.

The better we understand how stories unfold in our bodies, the more

equipped we are to thrive in the story-rich environment of the

twenty-first century.

Punched in the gut

Imagine your attention as a spotlight. When someone tells you a story, they are attempting to control that spotlight. They are

manipulating you.

We all do this every day, all the time. You try to hold attention as

you tell a story to coworkers over coffee; I’m trying to hold your

attention as I tell the story of the science of storytelling.

There are many different ways to draw the spotlight of other people’s

attention—and all of them instinctively or deliberately tap into basic

human drives. Here, for example, is a very short story attributed to

Ernest Hemingway.

For Sale: Baby shoes, never worn.

How does this story make you feel? I can speak for myself: When I first

encountered it as an undergraduate, my attention was instantly captured.

And when I realized, after a beat, what it meant, I felt punched in the

gut.

The story works because it triggers our natural negativity bias—that

is, the hardwired human tendency to focus on the bad, threatening,

dangerous things in life. It specifically activates the fear and despair

we’d feel if our child died, even if we don’t yet have one of our own.

We’re really good at focusing the spotlight of our attention on what

might hurt us—or hurt those close to us, especially our children. What

happens in our bodies when we throw the spotlight on a threat? We get

stressed out.

And what’s stress? That’s a tool nature gave us to

survive lion attacks—in other words, stress mobilizes our body’s

resources to survive an immediate physical threat. Adrenaline pumps and

our bodies release the hormone cortisol, sharpening our attention and

boosting our strength and speed.

But unlike other animals, humans have the gift and the curse of being

susceptible to stress even when we don’t face a direct physical threat.

This we do by telling ourselves, and each other, stories. They are the

best way we have to communicate potential threats to other humans—and

help each other to prepare for overcoming those threats.

Most of us will never face a flesh-and-blood lion, yet in stories we

transform lions into potent symbols of beautiful death. That’s the

essence of many stories: facing and overcoming dangers, which will

persist, multiply, and mutate in our minds and, in some cases, become

metaphors for more-immediate dangers.

As Neil Gaiman writes in his novel

Coraline:

“Fairy tales are more than true: not because they tell us that dragons

exist, but because they tell us that dragons can be beaten.”

When someone starts a story with a dragon, they’re harnessing

negativity bias and manipulating the stress response, whether they

intend to or not. We’re attracted to stressful stories because we are

always afraid that it could happen to us, whatever “it” is—and we want

to imagine how we would deal with all the many kinds of dragons that

could rear up in our lives, from family strife to layoffs to crime.

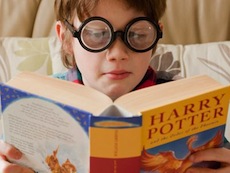

But we don’t necessarily need dragons to capture attention, right? At

the very beginning of J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series, she slowly

introduces us to a babe, alone in the world, under constant threat. We

instinctively take the side of the “boy who lived” because at the

beginning of the story, he’s so vulnerable.

Most of the Star Wars films take

another approach, by trying to inspire a

sense of awe—the emotional reaction to something so vast we can’t immediately grasp it—which research shows triggers behaviors

associated with curiosity, like turning to other people for answers.

How stories unfold in our bodies

While authors can capture our attention in many different ways,

sooner or later a villain will appear and a conflict will develop.

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone

may start gently, but Lord Voldemort looms in the background. As the

action rises and Harry’s society of witches and wizards slides toward

civil war, our attention sharpens and our bodies release more cortisol.

If that doesn’t happen, a story loses us. Our spotlight turns to

something else.

But cortisol alone isn’t enough to keep our bodies engaged with a

story. The conflicts in Harry Potter and Star Wars grab our

attention—and the settings can inspire awe and wonder—but they wouldn’t

involve us nearly as much if they didn’t also include characters we come

to care about.

As we see fictional characters interact, our bodies tend to release a neuropeptide called

oxytocin,

which scientists first found in nursing mothers. Oxytocin has

subsequently turned up in studies of couples and group-bonding—indeed,

we find oxytocin whenever humans feel close to each other, or even just

imagine being close. That’s why stories trigger oxytocin: When Princess Leia finally told Han Solo that she loves him in

The Empire Strikes Back, your body almost certainly released at least a trace level.

That’s not all that’s happening as we become involved in a story and its

characters. The brain activity of both storytellers and story listeners

starts to align thanks to

mirror neurons,

brain cells that fire not only when we perform an action but when we

observe someone else perform the same action. As we become involved with

a story, fictional things come to seem real in our bodies. The

storyteller describes a delicious meal and the listener’s mouth can

start to water. When the characters in the story feel sad, the

listener’s left prefrontal cortex activates, suggesting that they feel

sad as well.

As the plot thickens, the good author pushes the characters we care

about into conflict with the villain. Our palms sweat, we grip the hand

of the person next to us—who is likely having the same reaction. We

might feel the tension in our neck. Our body is braced for a threat, but

the threat is completely imaginary.

That’s when the storytelling miracle comes to pass: As the cortisol

that feeds attention mixes with the oxytocin of care, we experience a

phenomenon called “transportation.” Transportation happens when

attention and anxiety join with our

empathy.

In other words, we’re hooked. For the duration of the story, our

fates become intertwined with those of imaginary people. If the story

has a happy ending, it triggers the limbic system, the brain’s reward

center, to release dopamine. We might be overcome by a feeling of

optimism—the same one characters are experiencing on the page or screen.

Where do we end and where does the story begin? With the most intense, involving stories, it’s hard to tell.

How stories bring people together

At the beginning of the series, Harry Potter is extremely vulnerable. This inspires protectiveness in the reader.

At the beginning of the series, Harry Potter is extremely vulnerable. This inspires protectiveness in the reader.

Why in the world would evolution grant us this

ability? Why would nature actually make us crave stories and make

transportation a pleasurable experience?

I’ve already suggested part of the answer: We need to know about

problems and how to solve them, which can enhance our survival as

individuals and as a species. Without a problem for the characters to

solve, there is no story.

But there might be other reasons. Recent

research suggests that this process of transportation in fiction

actually increases our real-life empathic skills. Studies published in

2013 and 2015 exposed people to literary fiction or high-quality TV—and

then gave them the “mind in the eyes” test, in which participants look

at letterboxed images of eyes and try to identify the emotion behind

them. In the

2015 study, participants who watched

Mad Men or

The Good Wife scored significantly higher than did those who watched documentaries or simply took the test without first watching anything.

In other words, the empathic skills we build with stories are

transferrable to the rest of our lives: They are advantageous in

real-world situations where it helps to have insight into what another

person is thinking or feeling—situations like negotiating a deal, sizing

up a potential enemy, or understanding what our lover wants.

All these qualities make stories adaptive, in evolutionary terms.

They’re not just nice to hear. They can actually increase our chances of

survival.

How stories change behavior

Research finds that stories shape our behavior in other ways that can help us to thrive.

Study after study after study finds that stories are far more persuasive than just stating the facts. For example,

one found

that a storytelling approach was more effective in convincing

African-Americans at risk for hypertension to change their behavior and

reduce their blood pressure. A

study of low-performing science students found that reading stories of the struggles of famous scientists led to better grades. A

paper published last year found that witnessing acts of altruism and heroism in films led to more giving in real life.

Indeed, stories actually seem to trigger the neurochemical processes

that make certain kinds of resource-sharing possible. This biological

activity can lead to profound behavioral changes, including costly acts

of altruism.

When Claremont Graduate University economist Paul Zak and colleagues

showed a dramatic film of a father and son struggling with cancer, they

found that both cortisol and oxytocin spiked in nearly all of the

viewers—and that most of them donated a portion of their earnings from

the experiment to nonprofits. This didn’t happen in participants who

watched a simple film of the father and son wandering around a zoo. In

fact, the researchers found that the more cortisol and oxytocin

released, the more likely participants were to make charitable

donations—and in one experiment, Zak found that hormone levels predicted

donations with 80 percent accuracy.

This is the neurochemical process that makes fundraising and taxes

possible—and inspires people to mobilize large-scale support for

enterprises like political campaigns, churches, universities, libraries,

or, for that matter, the United States as a nation. Stories enable us

to form relationships with strangers and ask them to make small

sacrifices for something that is larger than themselves.

I picked Star Wars and Harry Potter as examples because those are

“master narratives” that have been embraced by, without exaggeration,

billions of people. There’s something awe-inspiring about the idea that

those stories have changed so many people right down to the molecular

level, all of them together feeling that spike of cortisol when Darth

Vader appears or that soothing flow of oxytocin when Hermione throws her

arms around Ron after they escape some Death Eaters, our bodies

resonating with each other across time and distance. These global

narratives don’t just entertain; they also impart ideals of heroism,

compassion, and self-sacrifice.

The dark side of storytelling

But this process has a dark side. Darth Vader and Lord Voldemort do

not exist in our world, but there are certainly people who wish us

harm—and, as the story of Anakin Skywalker so well reveals, there’s a

shadow-self inside all of us that is capable of wishing harm on someone

else.

A spike in cortisol can make us aggressive—one half of the “fight-or-flight” response we hear so much about—and

oxytocin has been implicated

in competition between groups. People dosed with oxytocin in the lab

show strong preferences for their own in-groups, however defined, from

school bands to fraternities. Oxytocin appears to play a role in trying

to take what out-groups have. People dosed with oxytocin are also more

likely to indulge in group-think—going along with collective decisions

even when they believe those decisions are wrong.

In short, stories form groups, a process enabled by oxytocin. It is

no accident that communities—fandoms—have sprung up around Harry Potter

and Star Wars, sometimes in (mostly) playful competition with each

other. It’s harmless fun for fans, but not all stories are as benign as

these, in intent or outcomes. Stories can carry us toward ideals that

are destructive, especially to out-groups. Stories are a form of power

over bodies, but it’s a power that we can use or misuse.

Take a look at this video, below, contrasting the speeches of two

political leaders—both expert communicators—about the nuclear bombing of

Hiroshima. And as you watch the video, think about their intentions.

What emotions are they aiming to stir in their audiences? What kind of

emotions do they trigger in

you?

I’m not trying (here, at least) to tell you who to vote for in November.

But given the power of stories, it’s dangerous to hear them without

asking ourselves what reactions they are triggering in our bodies. Mr.

Trump’s speech causes my stomach to clench and my mouth to go dry; in

asking me to put my own group ahead of others, he triggers anger and

anxiety. I believe that’s his intent. President Obama’s speech urges me

to reflect and to think compassionately about all of humanity. His words

lift my heart, just a bit—and, again, I believe that’s intentional.

I can feel their words in my body, but I’m not helpless against them.

Research also suggests that people are more than capable of defending

themselves against the power of stories. We can cognitively override the

emotional identification and transportation stories trigger by trying

to balance them against the facts. In cultivating awareness of the

impact of a story, we can tell a different one, or revise the story to

fit the facts or our own experience. We live in an story-saturated

world—coming at us through screens as well as through pages and

performances and music—and today, I think it’s essential for us to

understand all the ways in which leaders and organizations are trying to

manipulate us into believing what they want us to believe.

A lot of psychotherapy these days involves getting people to pay

attention to the stories they tell themselves. In therapy, we are told

to ask ourselves: Am I telling myself a story that helps me to grow and

flourish, or is it one that diminishes my life’s possibilities? We need

to do the same to stories other people tell us.

More than that, we need to look at our own responsibility for the

well-being of others, and cultivate awareness of the impact of our own

stories, of our own power over the bodies of other people. What

intentions do we bring to the stories we tell? Are we using our power to

lift people up and help them to see solutions to the problems we face

as individuals and as groups? Or are we using our power to reveal the

worst in ourselves, and so pit people against each other? Do we

communicate things that make us feel good about ourselves—or that make

us feel worse?

Stories bring us together, but they can also tear us apart. They can

bring us joy but they can also incite hatred. We are all born with the

power to tell stories. It’s a power we need to learn to use well and

wisely.

This essay is based on a talk for the Berkeley Communications Conference, delivered on June 1, 2016.

Original text : https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/science_of_the_story

© jonapotkivanunk.hu

© jonapotkivanunk.hu